President Donald Trump’s recent statement against his pre-born neighbor has sparked quite the moral dilemma for those who seek to see abortion ended. Trump’s comments affirmed that his view is that baby murder should continue under the guise of states’ rights, with exceptions for rape, incest, and situations where babies’ lives are secondary to winning elections. These statements have brought about the dilemma of whom to vote for—or not vote for—in the upcoming election.

So how should an Abolitionist vote? I believe there are two defining factors that we must consider when addressing this question. The first is that an abolitionist is a Christian, and the second is that an abolitionist is an immediatist. Both of these should weigh heavily in the hearts and minds of abolitionists as they eat or drink and certainly as they go to the voting booth. The problem is that American politics and culture have been thoroughly marinated in humanism and incrementalism. This indoctrination makes it difficult for many to properly think through the issue of voting, especially in casting a vote for the highest office in the land.

Before we look at how an abolitionist ought to think through every moral dilemma, I want to briefly go over what our culture has ingrained into nearly every person, abolitionist or not, in how to think through moral dilemmas and especially how to think through voting.

Situation Ethics and Incrementalism

In America, nearly everyone thinks through moral dilemmas through the moral framework of what is called Situation Ethics. This ethic is not Christian at all; it is humanistic in nature and was popularized by Dr. Joseph Fletcher. Fletcher lived from 1905 to 1991, and for 26 years, he taught Christian ethics at Harvard Divinity School and Episcopal Divinity School (affiliated with Union Theological Seminary), in Cambridge, Massachusetts. In 1974, Fletcher was named Humanist of the Year by the American Humanist Association, and in 1983, Humanist Laureate by the Academy of Humanism. Fletcher’s greatest influence came in 1966 when his book Situation Ethics: The New Morality was published.

This “New Morality” that Fletcher introduced into the church was nothing new, but it certainly made a lasting impact. Fletcher asserted that there were only three types of ethics that the Christian could choose from: 1. Law Ethics (ethics rooted in the immutable commands of God), 2. Antinomian Ethics (ethics detached from laws and based on personal desires), 3. Situation Ethics (ethics that are based on what was most loving in a given situation).

This third type of ethic was presented as a middle ground between the previous two. This is where incrementalism and Situation Ethics start to overlap. Incrementalism proposes a good goal but insists on meeting in the middle until you eventually get there. Of course, if you are an abolitionist, you are most likely already under the conviction that compromising with evil will never bring you closer to righteousness, but this mushy middle ground is where both situation ethics and incrementalism seek to reside—between what God has said is right and what God has said is wrong.

Another crossover between situation ethics and incrementalism is the principle of pragmatism. Fletcher outlined four presuppositions of situation ethics in his book, and the very first one was pragmatism: the ends justify the means. The ends justifying the means is, of course, the heartbeat of incrementalism, “If it just saves one life, it is worth it.” The plea of pragmatism is what is behind every 20-week ban, 12-week ban, and fetal heartbeat bill that has ever been presented. You could say that situation ethics demands this type of pragmatism in elections and incrementalism demands it in policy.

Of course, the greatest similarity between situation ethics and incrementalism is that love—not law—is the moral axiom. Every incrementalist bases their decision-making by asking the question, “What is most loving?” And every situationist does the same thing. This seems like a great question to ask, but it is actually quite deadly for both the pre-born and your conscience.

You see, Fletcher used love to justify infidelity, lying, abortion, and infanticide. To him, it all depended on the situation; then you would weigh out the consequences, and finally, you would compromise to a place where it would seem to be the “most loving.” This is exactly what incrementalists do. They observe the political climate, weigh out the consequences of losing an election, and compromise their position because it is the “most compassionate” thing to do.

The Abolitionist’s Ethic

I once asked Pastor Cary Gordon how he would define situation ethics, and this is how he responded:

“Situation ethics is where a person temporarily turns their back on God’s law during a particular situation where it is assumed that obeying it will not produce the preferred outcome. The subjective act of situationism is nearly always dishonestly described as ‘choosing the most loving thing to do’ after a flawed and sinful person presumes to pass judgment against God’s perfect law, declaring it ‘too harsh’ for application in a particular situation.” – Rev. Cary Gordon

This definition points out what is wrong with situation ethics and starts to point us in the right direction for how an Abolitionist ought to think through every moral dilemma. As Christians, we should never enter a moral dilemma and ask, “What is the middle ground between right and wrong?” or “What will the outcome be?” or “What would be most loving?” A Christian must approach every moral dilemma with a laser-like focus on the question, “What is right according to God?” And then the Abolitionist must demand obedience to that standard. This demand, in most situations, is of himself, but it continues out to others depending on the dilemma. This is why Abolitionists demand that child slaying halt.

Consider, if you will, the account of Daniel refusing to eat the king’s meat (Daniel 1). Daniel was taken captive, given a new name, and then was commanded to eat the king’s food. While the text doesn’t specify if this food was specifically forbidden because it was unclean or because it was sacrificed to idols, we do know for certain that it violated the conscience of Daniel, and he therefore refused to defile himself with the portion of the king’s meat. Daniel also refused to violate this conviction when the chief eunuch pointed out that it could cost both he and Daniel their heads. From this, we can see that Daniel formed his decision-making on the law of God, uncompromisingly refused to defile himself, and even allowed others to face danger based on his conviction to stand for what was right according to God.

Daniel didn’t approach the matter asking if the ends would justify the means, he didn’t try to make some kind of compromise only eating the king’s food on Tuesdays and Thursdays, and most assuredly didn’t ask what would be the most loving thing to do for himself or his boss (the chief eunuch). Daniel clearly asked the question, “What has God declared right?” And then he acted accordingly.

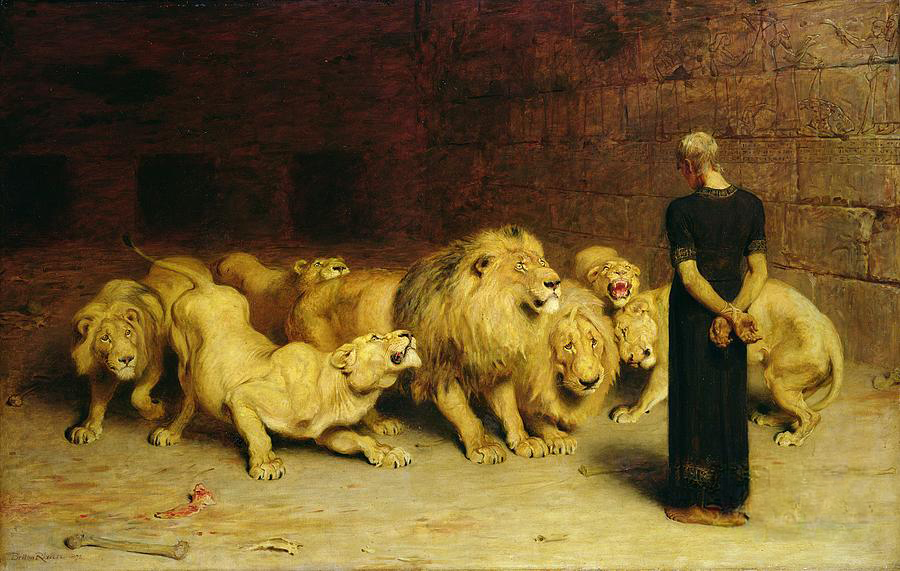

This approach is what his three friends had when faced with the fiery furnace, what Daniel held to when threatened with the lion’s den, and is what every Abolitionist should have. We ought to approach every moral dilemma asking what God has said is right, then we ought to demand immediate obedience to that standard in our own life, and from the outpouring of that obedience should come a demand for others to do what is right. While I call this the Abolitionist ethic, it really is the Christian ethic.

How Should an Abolitionist Vote?

Now, how should an abolitionist approach voting? Should he enter the ballot box looking at two candidates and make the lesser candidate the standard by which he is to make his decision? Should he ask the question, “What would be most comfortable for myself and my kin moving forward?” Should he seek to find some middle ground between God’s standard and sin? Certainly not! An Abolitionist should approach voting like he does every other moral dilemma.

In Exodus 18:21, God abbreviates His standard for elected civic leaders and gives us four basic criteria: “Moreover, you shall select from all the people able men, such as fear God, men of truth, hating covetousness; and place such over them to be rulers of thousands, rulers of hundreds, rulers of fifties, and rulers of tens.”

Every vote you cast ought to be in submission to this command, and every candidate you vote for ought to be 1. Able, 2. Fear God, 3. Speakers of truth, and 4. Hate covetousness (not given to bribes).

To fear God, one must protect the innocent and defend the fatherless. Our pre-born neighbors not only qualify but are first on both of those lists. Any candidate that openly opposes abolishing abortion is not worthy of your vote. It doesn’t matter what the consequences are—the ends don’t justify the means—it doesn’t matter how much more comfortable one candidate’s win would make you or your family. All that matters is what God has commanded, and that we demand obedience to that command.

There is no room within the Abolitionist framework to vote for men like Donald Trump, unless, of course, they repent. So let us remain faithful to God, pray for President Trump’s repentance, and burn with a holy fire to rescue our pre-born neighbors.